Working at the High Desert Museum always brings the unexpected, from photographing a river otter to donning attire from 1904. Recently, I walked into a classroom and found a group of adults laser-focused on making scat.

Working at the High Desert Museum always brings the unexpected, from photographing a river otter to donning attire from 1904. Recently, I walked into a classroom and found a group of adults laser-focused on making scat.

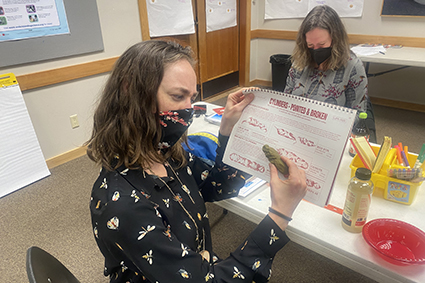

Scat is a scientific term for wildlife droppings – poop. Each adult was hunched over a small pile of brown clay carefully molding and shaping it to replicate their chosen animal. For a touch of accuracy, there were also feathers, seeds and other food remnants to attach to the miniature sculpture.

The task and its greater purpose was later explained to me by a coworker leading the activity, Sara Pelleteri, the Museum’s associate curator of STEM education.

But first, what exactly is STEM?

STEM education is focused on science, technology, engineering and math, and the High Desert Museum was a proud recipient in July 2021 of the National Science Foundation Sustaining STEM Grant. The $1.2 million grant goes to the Museum and three partners to co-lead a new education program bringing critical learning to rural students and their families. The other partners include the Oregon Coast Aquarium in Newport, The Wild Center in Tupper Lake, New York and Caddo Mounds State Historic Site in Alto, Texas.

One-quarter of U.S. students reside in rural communities, yet rural youth are 50 percent less likely to engage in out-of-school STEM experiences than their urban counterparts. The work done with educators through the Sustaining STEM Grant aims to shrink that gap. The two-day workshop on which I intruded was just a sliver of that work.

Returning to the scat-making klatch, the activity was meant to spark a new appreciation for wildlife and motivate people to slow down and observe their environments. The sculptors were educators from the High Desert Museum, Oregon Coast Aquarium and other STEM professionals. They were learning that the size, shape and marks around scat are all key to identifying the wildlife that left it. The participants were meant to take the activity and remake it for their region, focusing on the habitats that surround them.

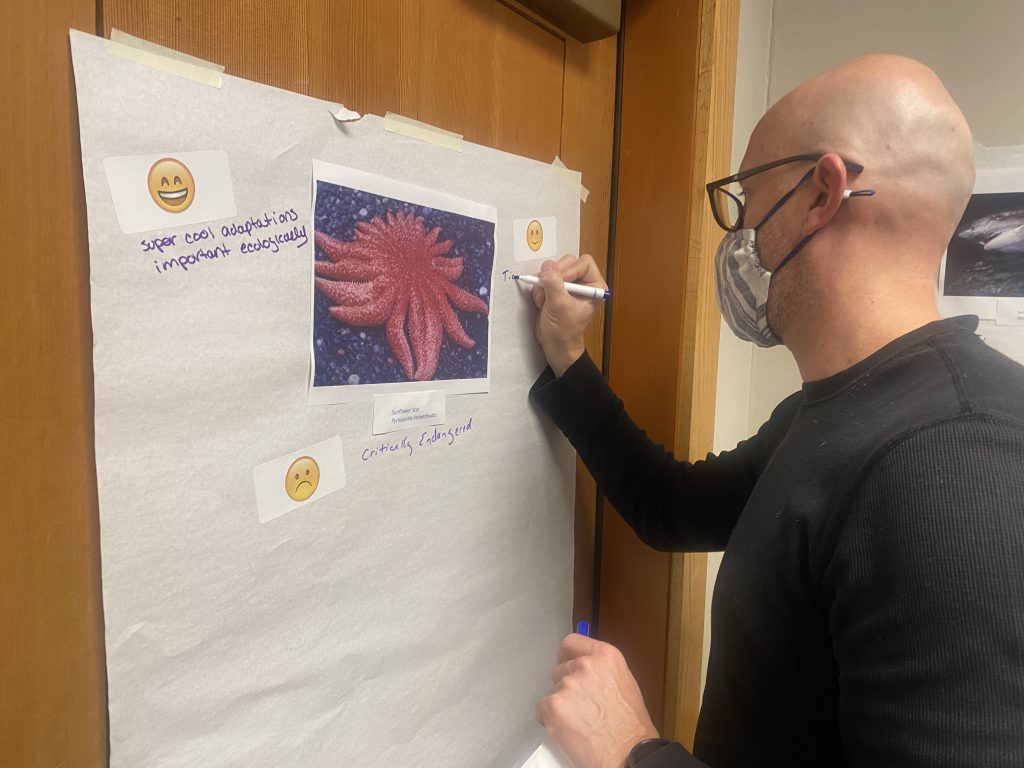

Another activity included in the workshop was aimed at transforming a person’s negative perception of a particular animal in the wild. Different creatures were labeled by the group with emojis, followed by a discussion on the animal’s role in their ecosystem. Through limited exposure, someone may have a negative perception of a wolf, but after learning about their role in keeping a balanced habitat, that perception may change.

Another activity included in the workshop was aimed at transforming a person’s negative perception of a particular animal in the wild. Different creatures were labeled by the group with emojis, followed by a discussion on the animal’s role in their ecosystem. Through limited exposure, someone may have a negative perception of a wolf, but after learning about their role in keeping a balanced habitat, that perception may change.

When I asked Sara Pelleteri about the project, I mistakenly called the material “clay.” I was corrected, and for good reason. Pelleteri made the substance at home, from scratch like any good baker. It contained flour, salt (a lot of salt), cream of tartar, water and dye. And it took her three attempts to get it right, from the color to the consistency.

To this group, it’s the little touches that make the program engaging. To say Pelleteri was proud of her “clay” is an understatement.

The future of the STEM grant work will include more idea-sparking workshops for educators, opening a wider world to rural students and families. Who knows what engaging activities I will walk in on next?