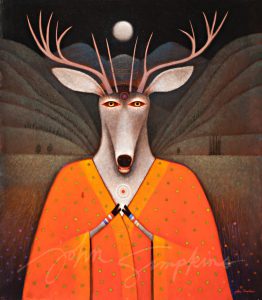

The exhibit Desert Mystic: The Paintings of John Simpkins opened at the High Desert Museum on October 27, 2018. The paintings reflect on the arid landscape and the wildlife surrounding his workspace in a schoolhouse in Andrews, Oregon. The exhibit opening was soon followed by a highly anticipated evening of conversation with Simpkins, filling the Museum’s Schnitzer Entrance Hall with more than 200 visitors eager to hear John discuss his artwork and life. The conversation continues here.

The exhibit Desert Mystic: The Paintings of John Simpkins opened at the High Desert Museum on October 27, 2018. The paintings reflect on the arid landscape and the wildlife surrounding his workspace in a schoolhouse in Andrews, Oregon. The exhibit opening was soon followed by a highly anticipated evening of conversation with Simpkins, filling the Museum’s Schnitzer Entrance Hall with more than 200 visitors eager to hear John discuss his artwork and life. The conversation continues here.

Painting in seclusion in the ghost town of Andrews, Oregon, how do you feel your artwork has evolved in the last seven years, being the town’s only human resident?

Painting is a life process. Living in the ghost town of Andrews, there are few distractions. I have learned to fully trust the intuitive guidance that leads me as I work, and I have released the constraints of time. Paintings evolve as days, weeks and months pass, eventually becoming something that is reflective of my observations, experiences and dreams. I have learned to trust what manifests as I paint. It evolves in each moment.

Some of your canvases are huge, larger than “Blood Moon” (9 feet x 10 feet) at the Museum. Do you find it takes more courage to approach a canvas the larger it is? Do you think it takes any courage to approach any canvas?

I have always been inspired by large canvases exhibited in museums and galleries. When I found myself here at this old one-room schoolhouse I felt it was time to explore this. What would it be like to paint on a canvas that was larger than me? Merriam-Webster defines courage as “mental or moral strength to venture, persevere, and withstand danger, fear, or difficulty.” Perhaps it takes a bit of courage, but mostly it is a marvelous challenge! It becomes much more physical, climbing up and down a ladder to reach the high places or being on my knees to work on the lower parts. It is an adventure! There is no fear, only joy and wonder!

Are there any creatures you’ve had contact with at and around the schoolhouse that you have not been able to paint? If so, what makes that creature different from the mule deer, cougar or badger?

Recently I have observed a group of bluebirds. They seem to be living inside the attic space of the old schoolhouse! They go in and out via a large hole made by a woodpecker and it is winter! There is snow! Yet there are five beautiful bluebirds here! There are magpies, so graphic in their black and white plumage! I may create something to do with this, we shall see. All creatures are marvelous and special to me.

When you spoke to the audience at the High Desert Museum in early November, you mentioned your morning espresso numerous times. It’s clearly an important part of your daily ritual. What kind of espresso do you drink?

It has indeed become a ritual of sorts! I like to sip my espresso from a small bowl, cradling the warmth in my hands. It brings many comforts! I use Organic II Espresso beans from THE BEAN organic coffee company purchased online via Amazon in 5-pound bags and brewed using a small stainless stovetop espresso maker made by Bialetti.

Looking to Steens Mountain every morning and having a front row seat for global climate change as the snow comes later and disappears earlier from the mountain top, are environmental issues taking a more prominent role in your work?

Yes. I am very concerned for our planet and all the precious lifeforms that have evolved here. Living alone with my dog, Ella, each day’s weather becomes the background for my work; I observe the changes and I feel a responsibility to share this in my work.

You document Andrews and the surrounding landscape with some amazing photos shared on Facebook. Have any of the photos inspired paintings? Or do you see your photos and paintings as separate work?

I do think of my photos and my paintings as separate work. It is a delightful challenge to capture the many moods of light and shadow, the weather and seasons of this place with my camera. Most of my photos are taken within the 2-acre parcel of land on which the old Andrews Schoolhouse and Teacherage are situated. My paintings are influenced by what I see and experience here, but I rarely use my photos as the basis for a painting.

How do you know when you’re finished with a painting?

The paintings let me know when they are finished. There is a clear sense that a painting has no further need for me! I may go out to the old schoolhouse ready to begin work, sit and look at the painting and realize that there nothing left to do. It is complete.

Do you see yourself leaving Andrews? After seven years of seclusion, where do you see yourself living and working after this?

I am open to new adventures, though there is no immediate need or desire in me to leave this magical old schoolhouse! I sense there are more stories to tell here. Yet, admittedly there is also a desire in my spirit to perhaps one day return to the southern part of France, to Arles, to find a place to paint and to work there for a month or two.

Find John online at johnsimpkins.com.

Just then, Mrs. Miller emerges from the root cellar where she’s just taken a bounty of potatoes harvested from the garden. She wipes her hands on her apron and her brow with her sleeve and looks around. She takes a moment to survey her family ranch, quietly contemplating the list of chores needing to be tended to on this brisk fall day. Mrs. Miller smiles at Emily, her son’s wife, before heading off toward the chicken coop to collect the day’s eggs.

Just then, Mrs. Miller emerges from the root cellar where she’s just taken a bounty of potatoes harvested from the garden. She wipes her hands on her apron and her brow with her sleeve and looks around. She takes a moment to survey her family ranch, quietly contemplating the list of chores needing to be tended to on this brisk fall day. Mrs. Miller smiles at Emily, her son’s wife, before heading off toward the chicken coop to collect the day’s eggs. Blending two women into one and adding in bits of her own personality allowed Linda to create a rich, full character that she’s able to connect with and comfortably portray to a wide-ranging audience. “Living history is an educational tool, and people learn best when they’re relaxed,” Linda said. “Being entertained puts people at ease. When I’m comfortable, and the visitor is comfortable, a sense of play emerges and then the interactive experience unfolds naturally.”

Blending two women into one and adding in bits of her own personality allowed Linda to create a rich, full character that she’s able to connect with and comfortably portray to a wide-ranging audience. “Living history is an educational tool, and people learn best when they’re relaxed,” Linda said. “Being entertained puts people at ease. When I’m comfortable, and the visitor is comfortable, a sense of play emerges and then the interactive experience unfolds naturally.” Often, the questions visitors ask require characters to have a personal timeline complete with important historical dates and dates marking personal milestones such as marriage and the birth of children or events such as moving to a new location. Mrs. Miller, who was born in 1845, traveled west with her family on the Oregon Trail when she was just 10 years old. She grew up near Salem and later fell in love with Mr. Miller. Together they moved to Central Oregon in 1881, pursuing the promise of free land. They established their homestead and ranch in 1882.

Often, the questions visitors ask require characters to have a personal timeline complete with important historical dates and dates marking personal milestones such as marriage and the birth of children or events such as moving to a new location. Mrs. Miller, who was born in 1845, traveled west with her family on the Oregon Trail when she was just 10 years old. She grew up near Salem and later fell in love with Mr. Miller. Together they moved to Central Oregon in 1881, pursuing the promise of free land. They established their homestead and ranch in 1882. Once a character has been created and developed, a sense of purpose needs to be determined. Not only is it important to decide why a character is at the Miller Family Ranch, but knowing what the character’s main role at the ranch is ensures authenticity of the entire scene and experience. Emily found that baking was a natural development for her character. Her pies often entice visitors of all ages to step inside the family cabin. “It’s not about me or my character,” Emily said. “It’s about the ranch. There is an outward focus on our visitors, on what they know, and what they want to know.”

Once a character has been created and developed, a sense of purpose needs to be determined. Not only is it important to decide why a character is at the Miller Family Ranch, but knowing what the character’s main role at the ranch is ensures authenticity of the entire scene and experience. Emily found that baking was a natural development for her character. Her pies often entice visitors of all ages to step inside the family cabin. “It’s not about me or my character,” Emily said. “It’s about the ranch. There is an outward focus on our visitors, on what they know, and what they want to know.” Her interest in the subject came to fruition over the past year. As Donald M. Kerr curator of natural history at the High Desert Museum, Louise dedicated herself to researching animal navigation and migration, talking to scientists from around the world and developing an interactive exhibit for the Museum’s visitors.

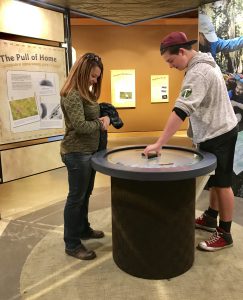

Her interest in the subject came to fruition over the past year. As Donald M. Kerr curator of natural history at the High Desert Museum, Louise dedicated herself to researching animal navigation and migration, talking to scientists from around the world and developing an interactive exhibit for the Museum’s visitors. The resulting exhibition, Animal Journeys: Navigating in Nature, investigates the internal mechanisms and biological forms of maps and compasses used by animals to find their way in the world and explores the techniques scientists are implementing to unravel these mysterious phenomena. It also shares insight into human impact on animals’ ability to navigate — such as how light pollution can obscure the night sky and completely disorient birds and other species — and offers ideas for effective conservation. And reflecting back on Louise’s initial inspiration, the exhibit examines how humans can read the landscape to navigate solely with natural cues.

The resulting exhibition, Animal Journeys: Navigating in Nature, investigates the internal mechanisms and biological forms of maps and compasses used by animals to find their way in the world and explores the techniques scientists are implementing to unravel these mysterious phenomena. It also shares insight into human impact on animals’ ability to navigate — such as how light pollution can obscure the night sky and completely disorient birds and other species — and offers ideas for effective conservation. And reflecting back on Louise’s initial inspiration, the exhibit examines how humans can read the landscape to navigate solely with natural cues. While there have been many major breakthroughs in scientific understanding — such as the discovery that dung beetles use the Milky Way for orientation in order to move in a straight line — much is still unknown.

While there have been many major breakthroughs in scientific understanding — such as the discovery that dung beetles use the Milky Way for orientation in order to move in a straight line — much is still unknown.

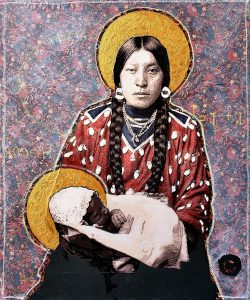

To broaden the story further and connect Curtis’s work to Native people’s lived experiences today, we asked three Native artists to comment on their art, its significance and the legacy of Edward Curtis. Pat Courtney Gold, a Wasq’u (Wasco) basket maker whose work is featured in the exhibition, commented that, “Art is part of my heritage. It is important for me and for Plateau people in general to see what we’re capable of reviving and the beauty of our heritage. Our heritage existed for thousands of years and speaks to us still.” Gold’s comments remind us of the importance of art as an expression of one’s identity and community and the significant role it can play in our lives.

To broaden the story further and connect Curtis’s work to Native people’s lived experiences today, we asked three Native artists to comment on their art, its significance and the legacy of Edward Curtis. Pat Courtney Gold, a Wasq’u (Wasco) basket maker whose work is featured in the exhibition, commented that, “Art is part of my heritage. It is important for me and for Plateau people in general to see what we’re capable of reviving and the beauty of our heritage. Our heritage existed for thousands of years and speaks to us still.” Gold’s comments remind us of the importance of art as an expression of one’s identity and community and the significant role it can play in our lives.

Butterflies offer much more than beauty. Along with bees, hummingbirds, moths, wasps and beetles, they are pollinators whose small stature belies their importance. Pollinators transfer pollen and enable many plants to produce fruits and seeds. This makes them vital to the reproduction of many native and commercial plants. Our native flowering plants are key to healthy soils and clean air and water. Plus, more than 150 different crops, such as apples,

Butterflies offer much more than beauty. Along with bees, hummingbirds, moths, wasps and beetles, they are pollinators whose small stature belies their importance. Pollinators transfer pollen and enable many plants to produce fruits and seeds. This makes them vital to the reproduction of many native and commercial plants. Our native flowering plants are key to healthy soils and clean air and water. Plus, more than 150 different crops, such as apples,