Responsible recreation benefits us all.

Like many people who are drawn to live in the West, I’m happiest when I’m out in nature.

Some of the best, most inspiring moments of my life have happened while running, hiking or horseback riding on trails. Here in Central Oregon, we are blessed with world-class recreation opportunities just outside our front doors. Outdoor recreation supports our health and wellbeing and brings economic benefits to the local community. I would rather see a packed trailhead than a packed shopping mall on a Saturday, as it indicates that folks are out experiencing and forging personal connections with nature — and will, hopefully, care more about it as a result.

But as Lauri Turner and Brock McCormick of the U.S. Forest Service recently discussed during one of our thought-provoking Natural History Pubs, while making humans healthier, recreation can harm wildlife and our public lands. Land managers must therefore balance their goals for recreation, habitat restoration and wildlife conservation. Most outdoor recreationists appreciate and respect the trails and the habitats they lead us through, but mounting issues include people dumping trash, leaving poop unburied, and forging new, unofficial trails. Some people also approach wildlife far more closely than animals can tolerate. While slightly less than 200 feet is felt to be an acceptable distance by recreationists, about 500 feet is the actual flight distance of mule deer, bison and pronghorn. Even those of us who set out with the best leave-no-trace intentions have unseen impacts on the many species who call the forest or desert home. We may contribute to soil compaction and erosion, tree-root damage, or cause deer to flee long before we spot them.

The decisions we make on the trail — and about which trails we use, and when — impact numerous species, from salamanders to elk. Wildlife responds best to predictable disturbances. For example, if trails get busy at certain times of day, they may learn to avoid, or at least expect, that disturbance, only returning during quieter times. If you roam far off trail in the early morning and meet a deer, it’s likely to be startled and make a hasty retreat. Body fat that the animal had stored for winter survival may end up being used for running, instead.

No-impact outdoor recreation doesn’t really exist, but low-impact recreation can! What can we do, as a community, to reduce our impact while continuing to enjoy our trails? A few actions to consider include:

• Keep to designated trails. We have enough official trails (not including user-created, BLM, Bend Parks and Recreation or State Lands) in the Deschutes National Forest for a person to hike 38 miles per weekend, May through September, without needing to repeat a single inch of trail.

• Respect seasonal restrictions in sensitive habitats.

• Give wildlife space. This is especially important when nesting or mating is occurring, and during the winter. Invest in a pair of binoculars, rather than getting too close.

• Try to keep your dog on a leash or under control. This is especially important during the winter and spring.

• Clear up your trash. Follow the Leave No Trace program, including Seven Simple Principles.

• Share responsible recreation tips with friends and family.

Please see the U.S. Forest Service’s website for further information about how we can reduce our impact on the flora and fauna that make this region so beautiful.

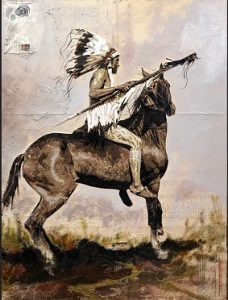

Ben Pease has been awarded the Jury’s Choice Award at the High Desert Museum’s Art in the West exhibition for his 2017 work “Honor and Respect Come to Thee”. It was among 226 pieces submitted in response to a nationwide call to artists for the Museum’s annual juried art exhibition and silent auction.

Ben Pease has been awarded the Jury’s Choice Award at the High Desert Museum’s Art in the West exhibition for his 2017 work “Honor and Respect Come to Thee”. It was among 226 pieces submitted in response to a nationwide call to artists for the Museum’s annual juried art exhibition and silent auction.

When the otter pup arrived at the Museum, he was a 6-week-old wiggly bundle of energy that tripped over his own feet when he followed after me. When he wasn’t running around and playing with his stash of toys, he was either napping or eating. With neither of us being experienced at bottle feeding, mealtime tended to result in a huge mess.

When the otter pup arrived at the Museum, he was a 6-week-old wiggly bundle of energy that tripped over his own feet when he followed after me. When he wasn’t running around and playing with his stash of toys, he was either napping or eating. With neither of us being experienced at bottle feeding, mealtime tended to result in a huge mess.

While overseas, Harry traded two packs of cigarettes for a Zeiss Ikon camera. As part of his military duties, he traveled around Japan, taking pictures everywhere he went. He even found his extended family, who he had visited once as a young boy. One day Harry and a friend packed a Jeep full of food, water and treats. They traveled several hours to deliver the supplies to Harry’s family. Conditions in Japan at the end of the war were dire, and his family credited Harry with saving their lives.

While overseas, Harry traded two packs of cigarettes for a Zeiss Ikon camera. As part of his military duties, he traveled around Japan, taking pictures everywhere he went. He even found his extended family, who he had visited once as a young boy. One day Harry and a friend packed a Jeep full of food, water and treats. They traveled several hours to deliver the supplies to Harry’s family. Conditions in Japan at the end of the war were dire, and his family credited Harry with saving their lives.