By Hand Through Memory will take you through the little known journey of the Plateau Indian Nations as they traveled from reservation confinement to the 21st century. This immersive exhibit highlights the experiences of Nez Perce, Umatilla, Warm Springs, Yakama, Spokane and Colville people.

Author: High Desert Museum staff

Spirit of the West

Spirit of the West offers an unforgettable walk through time. Your journey starts with a stroll past a Northern Paiute shelter and a fur trapper’s camp where all the historical details are depicted in incredible detail. Continue through the Hudson’s Bay Company fort, alongside an Oregon Trail wagon, through a hard rock mine, past a settler’s cabin and into the boomtown of Silver City.

Treading Lightly on Nature

Responsible recreation benefits us all.

Like many people who are drawn to live in the West, I’m happiest when I’m out in nature.

Some of the best, most inspiring moments of my life have happened while running, hiking or horseback riding on trails. Here in Central Oregon, we are blessed with world-class recreation opportunities just outside our front doors. Outdoor recreation supports our health and wellbeing and brings economic benefits to the local community. I would rather see a packed trailhead than a packed shopping mall on a Saturday, as it indicates that folks are out experiencing and forging personal connections with nature — and will, hopefully, care more about it as a result.

But as Lauri Turner and Brock McCormick of the U.S. Forest Service recently discussed during one of our thought-provoking Natural History Pubs, while making humans healthier, recreation can harm wildlife and our public lands. Land managers must therefore balance their goals for recreation, habitat restoration and wildlife conservation. Most outdoor recreationists appreciate and respect the trails and the habitats they lead us through, but mounting issues include people dumping trash, leaving poop unburied, and forging new, unofficial trails. Some people also approach wildlife far more closely than animals can tolerate. While slightly less than 200 feet is felt to be an acceptable distance by recreationists, about 500 feet is the actual flight distance of mule deer, bison and pronghorn. Even those of us who set out with the best leave-no-trace intentions have unseen impacts on the many species who call the forest or desert home. We may contribute to soil compaction and erosion, tree-root damage, or cause deer to flee long before we spot them.

The decisions we make on the trail — and about which trails we use, and when — impact numerous species, from salamanders to elk. Wildlife responds best to predictable disturbances. For example, if trails get busy at certain times of day, they may learn to avoid, or at least expect, that disturbance, only returning during quieter times. If you roam far off-trail in the early morning and meet a deer, it’s likely to be startled and make a hasty retreat. Body fat that the animal had stored for winter survival may end up being used for running, instead.

No-impact outdoor recreation doesn’t really exist, but low-impact recreation can! What can we do, as a community, to reduce our impact while continuing to enjoy our trails? A few actions to consider include:

• Keep to designated trails. We have enough official trails (not including user-created, BLM, Bend Parks and Recreation or State Lands) in the Deschutes National Forest for a person to hike 38 miles per weekend, May through September, without needing to repeat a single inch of trail.

• Respect seasonal restrictions in sensitive habitats.

• Give wildlife space. This is especially important when nesting or mating is occurring, and during the winter. Invest in a pair of binoculars, rather than getting too close.

• Try to keep your dog on a leash or under control. This is especially important during the winter and spring.

• Clear up your trash. Follow the Leave No Trace program, including Seven Simple Principles.

• Share responsible recreation tips with friends and family.

Please see the U.S. Forest Service’s website for further information about how we can reduce our impact on the flora and fauna that make this region so beautiful.

Turn Off the Lights for a Brighter Future

The Museum’s staff is thrilled to have recently become a partner of Lights Out Bend, a volunteer-operated education and advocacy program that seeks to highlight the issue of light pollution and inspire the community to reduce light pollution. In becoming partners, we join fellow local organizations keen to make a difference. This includes the Deschutes Public Library, East Cascades Audubon Society and Ruffwear.

What is light pollution and why should we care? Simply put, light pollution is the inappropriate or excessive use of artificial light, and human activities are lighting our night sky like never before. You’ve probably seen many businesses and homes leaving lights on at night. While this may seem harmless, it has major implications for native wildlife species. They evolved with predictable phases of light and dark, and many species are guided by celestial sources of light—such as the moon, stars and planets. Artificial lights interfere with these natural rhythms and behaviors. Bats, birds, moths and other species may suffer reduced hunting success, collisions with windows, disorientation and numerous other problems. Light pollution puts lives on the line.

Luckily, the solution comes with a simple flick of a switch! By turning off unnecessary lights, using motion sensor lights or lower intensity bulbs or installing fixtures that don’t direct light up into the night sky, we can improve the lives of birds and animals with whom we share the High Desert. We can also close our curtains at night to reduce the amount of light that can escape to the outside environment. While these actions are meaningful year round, they are particularly important during spring and fall migratory seasons.

Protecting the starry night sky saves wildlife. We also benefit from energy savings and a better view of the stars. It may even improve our health, as electric lights are thought to influence our own biological clocks. The Museum’s staff is committed to switching off all unnecessary lights at night. We hope you’ll join us.

For more information about this issue and what actions you can take to help, visit Lights Out Bend or the International Dark Sky website.

Telling Native American Stories Through Art

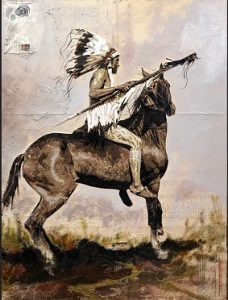

Ben Pease has been awarded the Jury’s Choice Award at the High Desert Museum’s Art in the West exhibition for his 2017 work “Honor and Respect Come to Thee”. It was among 226 pieces submitted in response to a nationwide call to artists for the Museum’s annual juried art exhibition and silent auction.

Ben Pease has been awarded the Jury’s Choice Award at the High Desert Museum’s Art in the West exhibition for his 2017 work “Honor and Respect Come to Thee”. It was among 226 pieces submitted in response to a nationwide call to artists for the Museum’s annual juried art exhibition and silent auction.

Ben is a young Native American artist whose work is deeply steeped in identity. Born on the Crow Indian Reservation in 1989, he has deep roots in both the Crow and Northern Cheyenne nations in southeastern Montana. While Ben has been making waves in the art world for several years now, he is currently working on his undergraduate degree at Montana State University with a major in Art and a minor in Native American Studies. Ben considers himself a storyteller by vocation, and feels strongly that he has a responsibility to tell the stories of Native people.

“Honor and Respect Come to Thee” is a mixed-media painting that shows a digitally manipulated historical photograph of a mounted Native American warrior superimposed on a rich and layered background composed of washes of acrylic paint, glass beads, antique ledger papers, an antique mail envelope and a US telegraph ticket. The dense but transparent surfaces of his paintings are somewhat hazy, and we get the sense that we are viewing an image from memory through the fog of time. His paintings are accumulations of meaningful materials and processes, where successive layers of later marks obscure earlier ones. The ledger pages remind us that we need to account for the past, and the acrylic paint almost becomes a kind of whitewash, which reminds us of our desire to avoid dealing with difficult and unpleasant aspects of our national history.

Composed as they are of historical images that are depicted using a combination of traditional painting techniques and modern, digital processes, Ben’s paintings elegantly express the tension between the traditional and the modern. His works are almost a tug-of-war between the past and the present, and his imagery is a rich stew of culturally-transmitted memory and history seasoned with the awareness of what it means to live in America as a Native person today.

What draws me to Ben’s work is his willingness to make art that can speak to difficult and painful aspects of the past while at the same time celebrating the positive elements of Native identity today. His work is a tribute to people who have been tested by great adversity, but have retained a strong sense of who they are and where they come from.

“Honor and Respect Come to Thee” and the other works in Art in the West are on view in the Brooks Gallery through August 26. The silent auction culminates at the High Desert Museum’s gala, the High Desert Rendzvous, that evening.

Photo: Honor and Respect Come to Thee by Ben Pease (Jury’s Choice Award)

Growing Up Otter

When the otter pup arrived at the Museum, he was a 6-week-old wiggly bundle of energy that tripped over his own feet when he followed after me. When he wasn’t running around and playing with his stash of toys, he was either napping or eating. With neither of us being experienced at bottle feeding, mealtime tended to result in a huge mess.

When the otter pup arrived at the Museum, he was a 6-week-old wiggly bundle of energy that tripped over his own feet when he followed after me. When he wasn’t running around and playing with his stash of toys, he was either napping or eating. With neither of us being experienced at bottle feeding, mealtime tended to result in a huge mess.

Cleaning up after these feedings started out as warm, shallow baths in the sink and a thorough towel drying afterwards to make sure he was warm and dry. As he became comfortable with the sound of the running faucet, the otter pup started sticking his face underwater and blowing bubbles, learning how to close his nose and small ears while in water.

As he grew, so did his love of water, and bath time moved from the sink to a tub. He started using his webbed toes and muscular tail to turn and spin. He went from holding his breath for barely a minute to holding it for three minutes, still a ways off from the nearly six minutes adult river otters can hold their breath.

Though otter pups in the wild are taught to swim by mom around 8 weeks of age, this slower lead up to swimming continued until our pup shed his thinner baby fur and grew in his denser and warmer adult fur around 11 weeks of age. An adult fur coat has 350,000 hairs per square inch and is made up of two layers: guard hairs and under fur. Their outer coat of water repellent guard hair helps prevent the insulating under fur from getting wet, which helps keep their bodies warm while they hunt for aquatic prey such as fish and amphibians all year round.

Since mastering a full bathtub of water, the otter has begun swimming in a large stock tank that allows him to practice swimming, diving, and catching small, live trout with his sharp claws and teeth. He’s also begun exploring the shallows in the museum’s stream habitat where he tosses around pebbles and chases after bugs.

Keep an eye on our Facebook page to follow along as the otter grows!

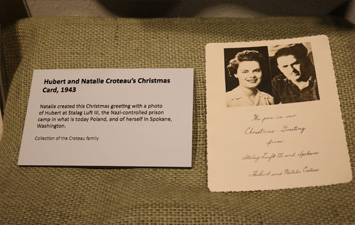

A Christmas card and a Camera: Objects with Stories to Tell

One of the most meaningful parts of working on World War II: The High Desert Home Front has been the opportunity to get to know veterans and their families. Our exhibit includes the stories, uniforms and personal belongings of four people who served during the war.

One of these soldiers is Hubert Croteau, a B-25 pilot. During his second mission, his plane was shot down over North Africa. Three of the men in his crew died in the crash. Croteau survived and was captured by German soldiers. They sent him to Stalag Luft III, a Nazi controlled camp for air force servicemen. Soon after, Hubert’s wife, Natalie, received a telegraph that he was missing in action. It would be another six weeks before she received news that Hubert was alive and had been taken prisoner.

Throughout Hubert’s imprisonment, he and Natalie exchanged letters, and Natalie sentpackages, including warm clothing. Despite the fact that conditions at Stalag Luft III were harsh—Hubert was often cold and hungry—the Nazi guards took pictures of the imprisoned Allied soldiers to prove that they were alive and in good health. Hubert sent one of these photos to Natalie. With it, she created a Christmas greeting that included a picture of herself inSpokane and Hubert in Stalag Luft III. This Christmas card is incredibly moving. Itis a testament to the strength of spirit of those on the front lines and those at home. After being imprisoned for 33 months, Hubert returned home and shared the next 64 years of his life with Natalie and their children.

Another favorite object is Harry Morioka’s camera. After spending a year incarcerated at the Tule Lake War Relocation Center, Harry was drafted into the U.S. Army’s unit of Japanese Americans. Because he was fluent in Japanese and English, he was selected for the Military Intelligence Service and stationed in Japan.

While overseas, Harry traded two packs of cigarettes for a Zeiss Ikon camera. As part of his military duties, he traveled around Japan, taking pictures everywhere he went. He even found his extended family, who he had visited once as a young boy. One day Harry and a friend packed a Jeep full of food, water and treats. They traveled several hours to deliver the supplies to Harry’s family. Conditions in Japan at the end of the war were dire, and his family credited Harry with saving their lives.

While overseas, Harry traded two packs of cigarettes for a Zeiss Ikon camera. As part of his military duties, he traveled around Japan, taking pictures everywhere he went. He even found his extended family, who he had visited once as a young boy. One day Harry and a friend packed a Jeep full of food, water and treats. They traveled several hours to deliver the supplies to Harry’s family. Conditions in Japan at the end of the war were dire, and his family credited Harry with saving their lives.

In 1946, Harry returned home. Harry and his wife, Kazuko, began the work of rebuilding their lives in The Dalles—before being imprisoned at Tule Lake, they had sold their home at a fraction of its value. They repurchased the house, paying well above marketvalue. Harry opened a business and became an active part of the community.

The Christmas card and camera are so special because of the stories they tell—stories of love and connection in the midst of hardship and war. Today, Hubert Croteau’s and Harry Morioka’s families are keeping these stories alive. Through them, these objects have much to say about American’s experiences during the war.

Sage Grouse: Icon of the Sagebrush Sea

My fascination with sage grouse began 20 years ago with an invitation by a friend to hunt the majestic greater sage-grouse with our falcons. I arrived in late November at his camp on the banks of the Sandy River in Wyoming, along a stretch peppered with Oregon Trail gravesites. This treeless, exposed stretch of river felt more like a moonscape than a center of a vibrant ecosystem. The Sandy flowed during the brisk, but sunny mid-day weather, but locked with sheets of ice during the -20F nighttime temperature — no doubt a brutal experience for the thousands of pioneers racing to beat the descending winter.

We were on the cusp of the ‘winter grouse’– a term used by falconers with a kind of spiritual reverence to describe the sage grouse, in their transformation to a near-immortal condition. While most gamebirds, like pheasants and partridge, suffer their highest mortality during the harsh winter months, the sage grouse seems to turn nature’s rules upside-down. Instead of huddling inside shrubby cover for warmth and protection, mid-winter sage grouse are found across exposed plateaus, browsing short-statured sage in 20 mile per hour winds and subzero temperatures. They not only survive, but they gain weight.

I heard stories of their winter congregations, and like many tales of “the good ol’ days”, I was skeptical. But the second day, my friend took me to the spot he estimated was the largest annual winter congregation of sage grouse in the species’ range. As we got out of the truck, you could see the heads of grouse peering over the sagebrush as far as you could see. Off in another direction, I shouted to my friend, “Ducks!?” pointing to a distant milling flock of birds 800 feet up in the sky, that probably numbered nearly a thousand. “No. Grouse,” he said. In yet another direction grouse were taking off from the sage and were so thick their wing-tips were slapping each-other. Within seconds, they were pin-dots over a large, distant butte. As we left the scene, hundreds of antelope filed over a ridgeline and a herd of wintering elk from the Wind River Range, held fast in the center of a huge sage-dominated flat. I was left stunned.

That exact spot is now home to the largest natural gas field in the world, the Jonah Field. This was the species’ stronghold–so the Jonah Field, to us, represented the beginning of the end. Yet in the years following this development, the conservation community engaged in the issue in a way never-before seen. Agencies, non-profit conservation organizations and private ranchers have pursued a collaborative approach to sage grouse conservation and restoration that holds significant promise. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is expected to make an announcement this September to decide whether or not the greater sage-grouse will be listed as threatened or endangered under the authority of the Endangered Species Act. Will a proactive, collaborative approach win the day or will regulation be the species’ safety net? Please visit Sage Grouse: Icon of the Sagebrush Sea and learn more about this pivotal species of the High Desert.

Photo courtesy Steve Chindgren

A New Delivery for the High Desert Museum!

In the midst of staff preparations for our 2015 summer season, our porcupine Honey had a baby!

A baby porcupine is called a porcupette (believe it or not). After a seven month gestation, they are born with their eyes open and all 30,000 or so quills in place, characteristics that set porcupines apart from many of their rodent relatives. The quills are soft at birth (which I’m sure mama appreciates), but they harden within a couple of hours after birth, providing the porcupette with some protection against predators.

Able to crawl soon after birth, the porcupette spends its first few days nursing, sleeping, moving about and hiding behind mom. Dads provide no care for their offspring. In this case, Thistle, the dad, was moved to another enclosure. For the first two weeks of life the porcupette nurses at night and will continue to nurse until four months old.

As an arboreal or tree dwelling rodent, a baby’s climbing instinct kicks in mere weeks after birth. They forage in trees and transition toward a strictly herbivorous diet that includes leaves, green plants, twigs and the cambium layer of trees.

Honey has taken to motherhood and is protective of her baby, often standing in between it and viewers who linger a little too long for her liking. As with wild porcupettes, our newest member usually hides out during the day and seeks shelter in a safe area on the ground while its mother retreats to the trees drawing attention away from her offspring. We’ve tried to minimize our handling of the porcupette and don’t yet know its gender.

Honey has taken to motherhood and is protective of her baby, often standing in between it and viewers who linger a little too long for her liking. As with wild porcupettes, our newest member usually hides out during the day and seeks shelter in a safe area on the ground while its mother retreats to the trees drawing attention away from her offspring. We’ve tried to minimize our handling of the porcupette and don’t yet know its gender.

A nocturnal animal, the porcupines are best viewed early morning or late afternoon in their exhibit outside of the Donald M. Kerr Birds of Prey Center.

Building the Past to Experience the Present

In Living History, we’re always looking for ways to bring our visitors back to the past. This gives them an authentic and memorable experience. One such experience is the sight, sound, and smell of a black powder musket being fired. For the fur trappers camp during Frontier Days (c. 1820) we had one small need: to build a brand new Northwest Trade Gun.

The Northwest Trade Gun itself is not an overly complicated or even hard to manufacture gun. On the contrary, it’s designed to be built quickly so that it can be traded for goods, thus it being named a “trade” gun. Make no mistake; building a gun is called gunsmithing for a reason. Even today when you buy a flintlock musket gun building kit, it isn’t as simple as opening the box, reading the instructions, putting part A into hole B and giving it a finished coat. It’s a gun kit, not a Lego set.

There are no “legosmiths”.

Crafting an older style gun is as much a test of skill as it is a test of patience. A modern day expert gunsmith can make a flintlock rifle from a kit in about 40 hours of labor time. That isn’t including the days, weeks or even months it takes to apply finishing coats and allowing them to dry. If you didn’t care about appearances, but just wanted a functional firearm? You’re still looking at a good 30 hours for your gunsmithing time. For someone who’s never attempted gunsmithing? Maybe 80 hours.

To build a Northwest Trade Gun you must drill and shape the wood and metal to your whim, even with a kit. Of course, a very solid grasp of mathematics is required for precision drilling, but you also must have the hands and fingers of an artist as you shape the stock to its desired form. Even with today’s modern power tools and equipment, this is a tedious process.

I, of course, had no idea what I was doing, so a good gentleman by the name of Jim Malloy took me under his wing and showed me the basics. Jim Malloy himself is the President of the Beaver State Historical Gunmakers Guild located in Prineville, Oregon. I foolishly assumed that the kit would come to us quite nearly completed and all that we would have to do is make it look pretty. I have never been so wrong in my life.

I, of course, had no idea what I was doing, so a good gentleman by the name of Jim Malloy took me under his wing and showed me the basics. Jim Malloy himself is the President of the Beaver State Historical Gunmakers Guild located in Prineville, Oregon. I foolishly assumed that the kit would come to us quite nearly completed and all that we would have to do is make it look pretty. I have never been so wrong in my life.

Regardless, the Trade Gun was finally finished, and I’m rather proud of the end result. Of course, I did make sure I wasn’t the first one to shoot it, though.