How do volunteer wildlife interpreters stay up to date in order to engage visitors? One way is through a volunteer book club. Each month we select a new title to read and discuss that relates to the daily talks we offer. Reading together helps improve our knowledge and enables us to better engage with visitors and respond to questions, not to mention that learning new things is interesting and fun! If you’d like to get in on what the Wildlife Team has been reading, here are a few titles we’ve looked at recently.

A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold. A must-read for anyone who loves wildlife and seeks to understand the history and current state of wildlife management in the United States. The seminal work of the “father of wildlife ecology,” this book is a collection of short essays where the author speaks of a land ethic and our moral responsibility to the natural world—a community to which we belong. Leopold’s sentiments have informed the work of the wildlife field and have much in common with how we hope to create connections to wildlife with our visitors.

A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold. A must-read for anyone who loves wildlife and seeks to understand the history and current state of wildlife management in the United States. The seminal work of the “father of wildlife ecology,” this book is a collection of short essays where the author speaks of a land ethic and our moral responsibility to the natural world—a community to which we belong. Leopold’s sentiments have informed the work of the wildlife field and have much in common with how we hope to create connections to wildlife with our visitors.

Path of the Puma: The Remarkable Resilience of the Mountain Lion by Jim Williams. If you live in the High Desert you are living with large carnivores, and mountain lions make the news on a regular basis. With our daily Carnivore Talk in full swing, interpreters regularly get questions about these “big cats.” Williams goes into detail about the natural history of the mountain lion, why they are important to the landscapes we all share and their conservation in our region and beyond. After reading this one, interpreters are ready to chat about cats with museumgoers.

Path of the Puma: The Remarkable Resilience of the Mountain Lion by Jim Williams. If you live in the High Desert you are living with large carnivores, and mountain lions make the news on a regular basis. With our daily Carnivore Talk in full swing, interpreters regularly get questions about these “big cats.” Williams goes into detail about the natural history of the mountain lion, why they are important to the landscapes we all share and their conservation in our region and beyond. After reading this one, interpreters are ready to chat about cats with museumgoers.

Animal Weapons: The Evolution of Battle by Douglas J. Emlen. Some of the more frequent questions we get about deer and elk are from visitors fascinated by their amazing antlers. The author of this book outlines his perspective as an evolutionary biologist working to understand the factors that can lead to an animal arms race, where species such as deer and elk may compromise their own health to grow out-sized and seemingly unnecessarily large weapons. Read it on your own or ask a volunteer to fill you in after the daily High Desert Hooves talk.

Animal Weapons: The Evolution of Battle by Douglas J. Emlen. Some of the more frequent questions we get about deer and elk are from visitors fascinated by their amazing antlers. The author of this book outlines his perspective as an evolutionary biologist working to understand the factors that can lead to an animal arms race, where species such as deer and elk may compromise their own health to grow out-sized and seemingly unnecessarily large weapons. Read it on your own or ask a volunteer to fill you in after the daily High Desert Hooves talk.

And a few more on the list –

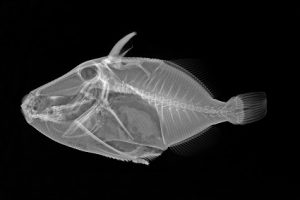

- The Fish in the Forest: Salmon and the Web of Life by Dale Stokes

- Hurricane Lizards and Plastic Squid: The Fraught and Fascinating Biology of Climate Change by Thor Hanson

- Fuzz: When Nature Breaks the Law by Mary Roach

- Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer

- Stronghold: One Man’s Quest to Save the World’s Wild Salmon by Tucker Malarkey

- Fur, Fortune and Empire: The Epic History of the Fur Trade in America by Eric Jay Dolin

- Collared: Politics and Personalities in Oregon’s Wolf Country by Aimee Lyn Eaton

- Rewilding Our Hearts: Building Pathways of Compassion and Coexistence by Marc Bekoff

- The Predator Paradox: Ending the War with Wolves, Bears, Cougars, and Coyotes by John Shivik

- Why Fish Don’t Exist: A Story of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of Life by Lulu Miller

- Nature’s Best Hope: A New Approach to Conservation That Starts in Your Yard by Douglas W. Tallamy

Of all the animals cared for at the Museum, raptors are perhaps what we are best known for. Twenty-eight nonreleasable birds call the Museum home, half of which participate in Raptors of the Desert Sky.

Of all the animals cared for at the Museum, raptors are perhaps what we are best known for. Twenty-eight nonreleasable birds call the Museum home, half of which participate in Raptors of the Desert Sky. Each day each bird can choose to participate in the program. It turns out raptors aren’t that different from people. They have stage fright. They get tired. They have bad days. They don’t have to fly if they don’t want to. Another can take their place. Some, like Pefa the peregrine, are fearless, confident and highly motivated. She rarely misses a show. Others, like Walter the golden eagle, can be shy and easily overwhelmed. They might only make occasional appearances. That’s okay, as it’s all about providing the highest possible welfare to the animals we care for while sharing them with our community, and it makes for a dynamic program.

Each day each bird can choose to participate in the program. It turns out raptors aren’t that different from people. They have stage fright. They get tired. They have bad days. They don’t have to fly if they don’t want to. Another can take their place. Some, like Pefa the peregrine, are fearless, confident and highly motivated. She rarely misses a show. Others, like Walter the golden eagle, can be shy and easily overwhelmed. They might only make occasional appearances. That’s okay, as it’s all about providing the highest possible welfare to the animals we care for while sharing them with our community, and it makes for a dynamic program.

The High Desert region has rich and varied cultural and artistic traditions. These artforms range from music, silversmithing and storytelling to Indigenous basketmaking and beadwork, Mexican charro roping and quilting. In academic circles, these traditional artforms are called folklife.

The High Desert region has rich and varied cultural and artistic traditions. These artforms range from music, silversmithing and storytelling to Indigenous basketmaking and beadwork, Mexican charro roping and quilting. In academic circles, these traditional artforms are called folklife.

Culture keepers, often referred to as folk or traditional artists, have strong cultural ties to their art forms, which they actively practice and work to preserve and pass on through presentations, demonstrations and performances. Culture keepers also work to pass down their artforms to younger generations to ensure their preservation.

Culture keepers, often referred to as folk or traditional artists, have strong cultural ties to their art forms, which they actively practice and work to preserve and pass on through presentations, demonstrations and performances. Culture keepers also work to pass down their artforms to younger generations to ensure their preservation.

One of the most common questions we get from visitors is about how the creatures, from river otters to desert tortoises, came to be in our care. And every day, I spend time with a small, new resident that came to us last summer, a Western painted turtle with a very interesting story.

One of the most common questions we get from visitors is about how the creatures, from river otters to desert tortoises, came to be in our care. And every day, I spend time with a small, new resident that came to us last summer, a Western painted turtle with a very interesting story. Because of the fragmentation of wild populations, introducing an individual to a new population could also spread disease that is found in one area to another. It is important to note that in the state of Oregon it is illegal to release wildlife that has been under human care for longer than 72 hours.

Because of the fragmentation of wild populations, introducing an individual to a new population could also spread disease that is found in one area to another. It is important to note that in the state of Oregon it is illegal to release wildlife that has been under human care for longer than 72 hours.