In celebration of Black History Month, we are looking back at recent programs exploring the Black experience in the High Desert.

This post is from February 2022.

The recent Hatfield Sustainable Resource Lecture featured Nikki Silvestri, one of The Root’s 100 Most Influential African Americans. She has traveled the world speaking about the intersection of ecology, economy and social equity, and is the founder and CEO of Soil and Shadow. We were honored to host her talk at the High Desert Museum.

Before the Civil War, Western states and territories became a battleground over the westward expansion of slavery and the status of free and enslaved Black people. In Slavery and Black Exclusion in the American West, professor Stacey Smith, a historian at Oregon State University, explores the enslavement of Black people in the West and African American resistance to slavery, as well as how both issues intertwined with anti-Black exclusion laws in Oregon and California.

Gwen Trice, the executive director of Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center in Joseph, Oregon, uncovers a previously hidden history in Maxville Today: Connecting our Past, Present and Future. Trice shares stories of African Americans during the Great Migration; Greek, Japanese, Filipino, Chinese, Hawaiian and Guamanian immigrants; and Native people against the backdrop of the timber and railroad industries. Join us on a journey and pack your bags for contemplation and conversation.

PARTNER PROGRAMS – Our partners are also offering thought-provoking programs this month.

The Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Quintet pays tribute to duke Ellington’s “Cotton Tail” during this video release on Tuesday, February 1 from 3:00 pm – 4:00 pm.

Art AfterWords: A Book Discussion from the National Portrait Gallery and DC Public Library will discuss the portrait of Ella Fitzgerald and discuss the related book “Seven Days in June” by Tia Williams, Tuesday, February 8 from 2:30 pm – 4:30 pm.

History Film Forum from the National Museum of American History is a video release of the new documentary Muhammad Ali: Documenting a Legend, Wednesday, February 9 from 3:00 pm – 4:00 pm.

(All times are Pacific Standard Time.)

The Father’s Group

The Father’s Group

Mission: To enhance the lives of children through education, leadership, and networking; while strengthening our community, eliminating barriers, and helping them reach their full potential.

Check out their February film series at Open Space Event Studios in Bend!

Friday, February 4 – I Am Not Your Negro

Sunday, February 13 – Hidden Figures

Friday, February 18 – Who’s Streets?

Friday, February 25 – Red Tails

Oregon Black Pioneers

Mission: To research, recognize, and commemorate the history and heritage of African Americans in Oregon.

Dive into the virtual exhibition Racing to Change: Oregon’s Civil Right’s Years. It illuminates the Civil Rights Movement in Oregon in the 1960s and 1970s, a time of cultural and social upheaval, conflict, and change. The era brought new militant voices into a clash with traditional organizations of power, both black and white.

Oregon Historical Society

Mission: To preserve our state’s history and make it accessible to everyone in ways that advance knowledge and inspire curiosity about all the people, places, and events that have shaped Oregon.

On Monday, February 7, the Oregon Historical Society and OPB will rebroadcast Oregon Experience: Oregon’s Black Pioneers. The program examines the earliest African-Americans who lived and worked in the region during the mid-1800s. They came as sailors, gold miners, farmers and slaves. Their numbers were small, by some estimates just 60 black residents in 1850, but they managed to create communities, and in some cases, take on racist laws — and win.

Working at the High Desert Museum always brings the unexpected, from photographing a river otter to donning attire from 1904. Recently, I walked into a classroom and found a group of adults laser-focused on making scat.

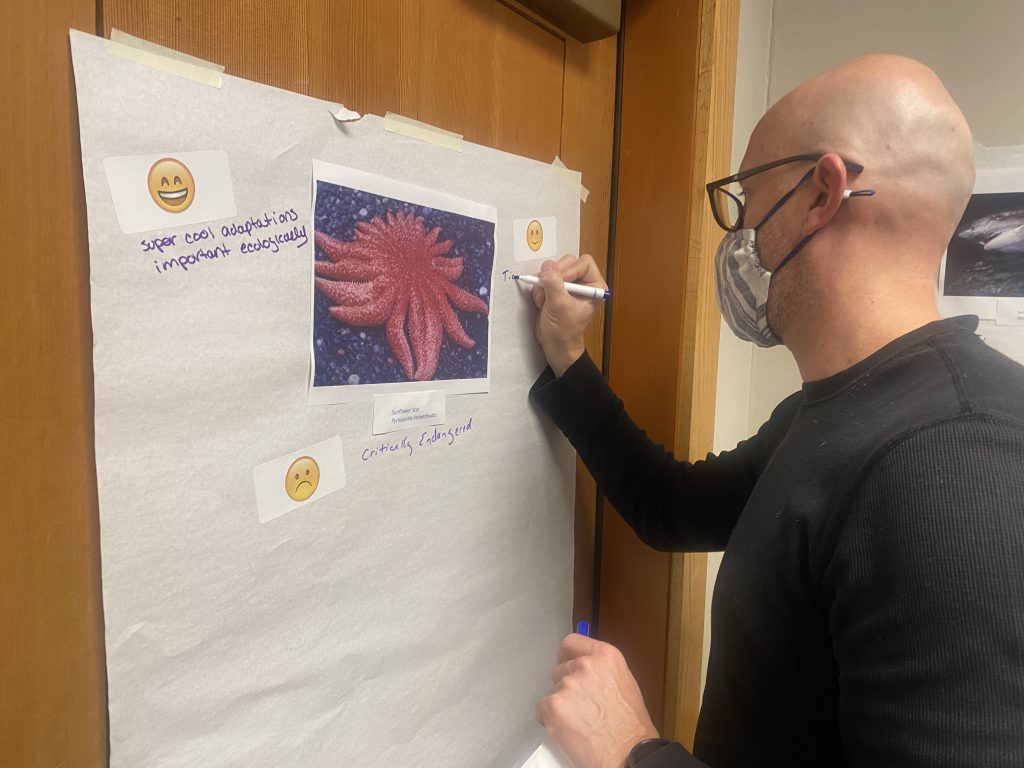

Working at the High Desert Museum always brings the unexpected, from photographing a river otter to donning attire from 1904. Recently, I walked into a classroom and found a group of adults laser-focused on making scat. Another activity included in the workshop was aimed at transforming a person’s negative perception of a particular animal in the wild. Different creatures were labeled by the group with emojis, followed by a discussion on the animal’s role in their ecosystem. Through limited exposure, someone may have a negative perception of a wolf, but after learning about their role in keeping a balanced habitat, that perception may change.

Another activity included in the workshop was aimed at transforming a person’s negative perception of a particular animal in the wild. Different creatures were labeled by the group with emojis, followed by a discussion on the animal’s role in their ecosystem. Through limited exposure, someone may have a negative perception of a wolf, but after learning about their role in keeping a balanced habitat, that perception may change.

The Father’s Group

The Father’s Group